A couple of days ago, I read an article in Open Magazine about Indian performance artist, Inder Salim cutting off his finger.

“One hot April morning, I chopped off the little finger of my left hand and threw it into the dead river called Yamuna. They call me crazy. But I call it art.”

Well quite.

It seemed quite a brave thing to do to make a point and I’m not going to give him a hard time for being so literal about highlighting the state of Delhi’s famous river.

The Yamuna is one of India’s greatest rivers. Holy to Hindus, The Imperial Gazetteer of India in 1909 mentions the waters of Yamuna distinguishable as “clear blue” as compared to silt-ridden yellow of the Ganges. Unfortunately, the Yamuna that runs through present day Delhi is an open sewer and clinically dead.

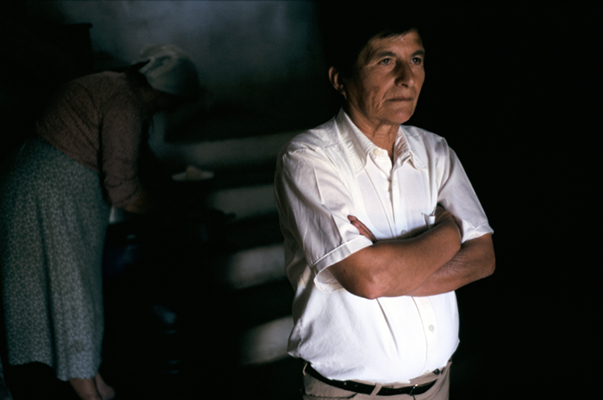

I was so intrigued by Delhi’s water situation a couple of years ago and made some work around it that became a film for More4 news. You can see the piece here.

The point was that Delhi’s water wasn’t in this hellish state as the result of appalling poverty – all those pesky poor people washing and cremating themselves in it – rather a complete lack of infrustructure around water management and wholescale pollution by industry. That hasn’t stopped the Delhi authorities evicting thousands of poor Delhi-wallahs that lived on its banks over the last few years.

There are perfectly sensible answers to the state of the Yamuna – Indian answers too. Brilliantly articulated by Sunita Narain, Director for the Centre for Science and Environment, she says: ‘A city will be more efficient if it collects water locally, supplies it locally and disposes waste locally’. There’s an excellent piece by her here.

Anyway, as Delhi looks forward to the 2010 Commonwealth Games, I’m hoping that someone will finally listen to Narain and the other Indian environmentalists, too numerous to mention, whose message about water, the city and sustainability has yet to seep into the murky waters of government. But I’m sure they will be able to smell it…